tackling crony capitalism with game theory & market analysis

As the United States backslides into corruption, it's time for us losers to form a pact

Eliminating corruption and bribery has long been accepted as beneficial to businesses, consumers, and the economy at large, as the pay-to-play model of cronyism imposes costs, lowers foreign investment, and fails to properly reward “good” management.1 Pro-capitalist business executives depend on external accountability and the rule of law to solve the tragedy of the commons problem that arises when individual firms are not discouraged from bribing government officials.

In line with bipartisan, pro-business ideology, state intervention to correct this market failure is fundamental to free market capitalism.2 Careful, incremental interventions that avoid government missteps are preferred over radically overhauling the economic system. Still, those of us in favor of better business behavior with respect to people and planet should recognize that our opponents are radically downsizing and debilitating democratic institutions, and plan to fill the vacuum with a pay-to-play system that lines their own pockets. The words of Adam Smith, “father of the free market,” are poignant:

“The statesman who should attempt to direct private people in what manner they ought to employ their capitals, would not only load himself with a most unnecessary attention, but assume an authority which could safely be trusted, not only to no single person, but to no council or senate whatever, and which would nowhere be so dangerous as in the hands of a man who had folly and presumption enough to fancy himself fit to exercise it.”3

Smith’s famous invisible hand remains a useful metaphor for market forces, but the rise of cronyism and “human hand” interference has resulted in an unfair and inefficient marketplace.

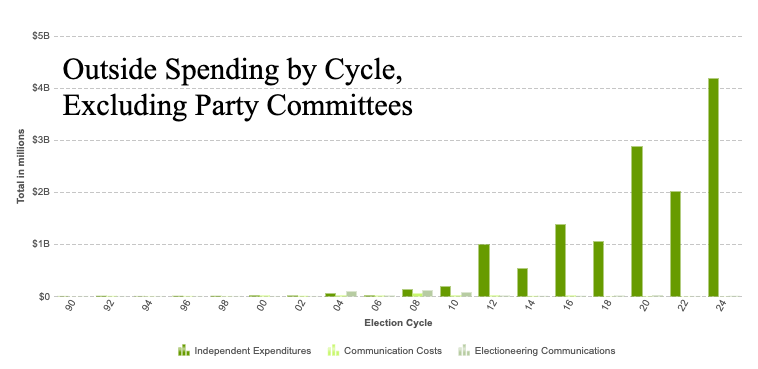

Good governance policies like the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and Sarbanes - Oxley Act gained traction from the 1970s through early 2000s. In part, these policies came as a response to political scandals and corporate malfeasance perpetrated in the Watergate and Enron/Arthur Anderson scandals. Laws that institutionalized ethical business practices were followed by a 2010 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission that found limits to corporate political donations unconstitutional on grounds of free speech. In the years since, outside political spending has skyrocketed, and fundraising pressures continue to distract elected officials from responding to constituent needs.4

As the U.S. economy adjusted to globalization, proposed reforms to implement legal standards for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and human rights violations have failed at the federal level. Over the past decade, industry lobbyists have downplayed the negative externalities of corporations to politicians, obscured them from the public, and largely abdicated responsibility.5 A lack of accountability raises doubt in the electoral feedback mechanism between voters and politicians and its conduciveness to reigning in corporate actors.

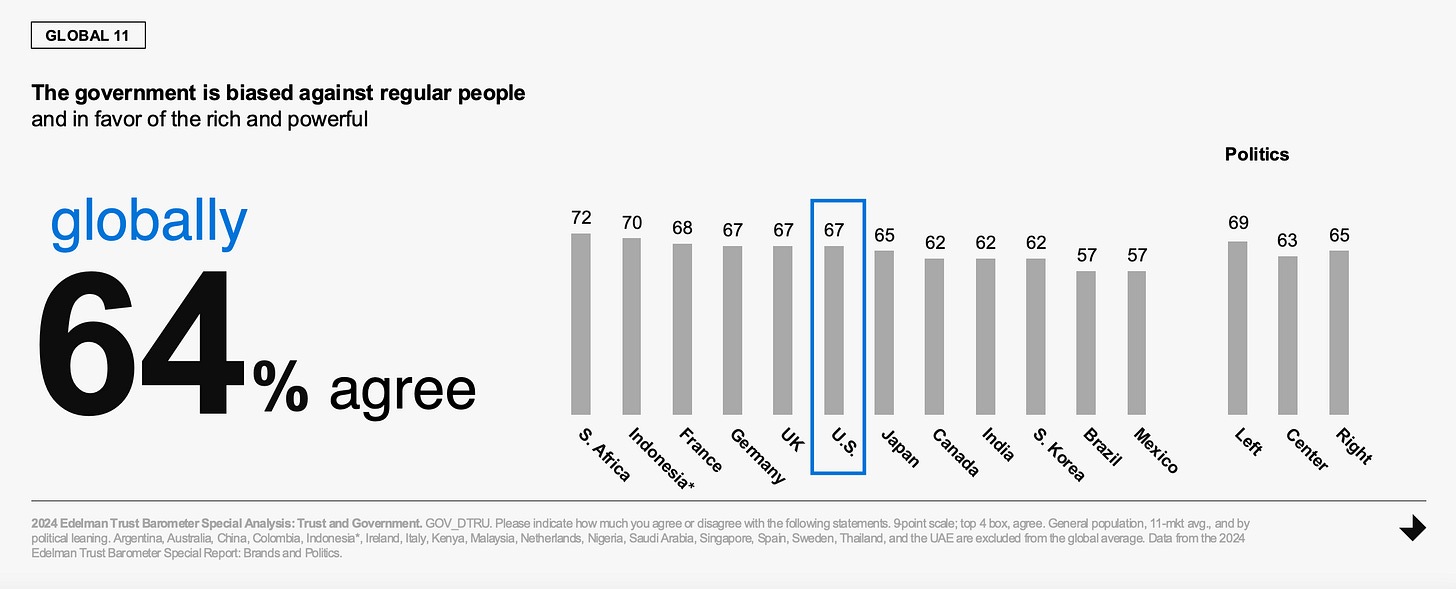

Trust in government is linked to partisanship, a phenomena taking place globally according to Edelman Trust Barometer’s 2024 analysis.6 An individual’s trust in government increases when their preferred party wins, and decreases when the opposing party wins. Politicized perception of government corruption has become detached from the reality that all politicians have opportunities and motivations to prioritize corporate and self interests over public interests. Though some U.S. officials, predominantly Democrats, have sworn off of corporate PAC money in an attempt to demonstrate public fealty, the distinction between ethical and corrupt officials is clouded by a hectic media environment and targeted disinformation.

Many elected members of Congress regularly buy and sell assets based on the privileged, asymmetric information they collect on the job, bursting any illusion of objectivity in decision-making. Bipartisan legislation to ban members and their immediate family from stock ownership was introduced with 29 House cosponsors and two Senate cosponsors in 2023, but both bills died in committee.

Perhaps the most troubling finding in Edelman’s analysis, is that our social fabric decays without government trust, as government distrusters are much more likely to prioritize “personal freedom” over “the common good.” This slump in altruism speaks to the hard-to-measure feeling that our interactions with one another have become increasingly self-interested. When it comes to solving societal problems that require cooperation, heightened independence is limiting.

The economic inefficiencies of crony capitalism are clear: when personal interests and relationships lead to noncompetitive markets, value creation is diminished. More importantly, though, the systemic harms of crony capitalism and government distrust are greater than the sum of each corruption and bribery occurrence. 67% of Americans believe that the government is biased against regular people and in favor of the rich and powerful, a clear sign that solidarity and sacrifice is not aligned with the collective consciousness of the nation. In a time when unified action is vital, our country is stuck in a cycle of government distrust, socially isolated behavior, and lack of progress on solvable problems. The government distrust narrative has become self-reinforcing, and breaking this cycle will require an anti-cronyism overhaul.

Disentangling cronyism from our political and economic systems would involve an investigative marathon, overcoming inertia, hurdles, and even political persecution. The most vulnerable in our communities already feel the heat from crony capitalism, and freedom to speak in defiance of an emboldened Trump administration is not guaranteed. Federal funding pauses have been planned for universities unwilling to exact race, gender, and the LGBTQ+ community from academic research and administrative policies.7 Political activists with legal-resident status have been arrested and held by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents without charges, under the antiquated Alien Enemies Act of 1798.8 We have already witnessed private firms including Meta and Deloitte change their policies based on executive orders that did not include mandates for businesses.9 These leadership decisions can and should be interpreted as currying favor with the current administration, setting up a quid-pro quo arrangement.

Fireproof, dynamic, and integrity-based democratic institutions are needed for the future, else firms will continue to compete on an inefficient and unfair playing field, and society will be burdened by unaccountable firms and truncated economic growth. This framing illustrates crony capitalism as an economic issue relevant to both the business community and public advocates, drawing a through-line between anti-cronyism and the economic rights described by Franklin Delano Roosevelt as “freedom from want.”10 We the people deserve to trust that our government officials do not accept bribes at the expense of our economic freedom.

Looking to long-term reforms, rebuilding democratic institutions that are unburdened by cronyism is prerequisite to achieving high global standards for human rights and environmental protection within business activities. Self-regulation has proven insufficient, and when legal violations can be covered-up with bribery, accountability is too easily evaded. In an under-regulated U.S. and global landscape, we are left to organize with players who come to the table of their own volition and firms complying with the European Union’s due diligence and reporting laws. Although firms take a risk by withdrawing from markets soiled by corruption in the short-term, committing to a rules-based system mitigates the greater long-term risk of eroded business value.

The counter-argument that businesses and CEOs should fly under the radar, or even pay into crony capitalism, to protect stock prices and avoid souring relationships with an administration’s regulators and contract-awarders, is shortsighted. Once first-movers have made bold public displays of allegiance to an administration, those with the greatest ability to pay subsequent bribes can outlast others, forming oligarchical structures, and bidding in an exclusive auction for tailor-made laws and access to public goods. In order to enter corrupt foreign markets, some multinational enterprises have developed corruption-navigating capabilities.11 These firms are well-positioned for a U.S. market backsliding into corruption. Corruption “distances” can help us better understand firms’ investment behavior, as firms from corrupt states have the capacity to bribe when necessary, entering markets regardless of the presence of corruption, while firms from less corrupt countries struggle to enter more corrupt markets.

The majority of firms, especially small and medium-sized firms, do not have capabilities to navigate the inside track to the Trump administration, nor the resources for staying power, and should recognize the high likelihood that they will “lose” in consecutive games of cronyism. By banding together as “losers” and advocates for integrity-based politics and democracy, we all stand a better chance at “winning” in the long-run. Even first-movers that respond to new regimes with flattery and donations would be wise to recognize that returns from cronyism eventually dilute and diminish, and that the United States’ economic security is endangered by crony capitalism. In a doomsday scenario, the anticipatory behavior of oligarchical firms and actors leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy. Highly-insulated firms and actors stand the best chance to survive a complete meltdown of the U.S. economy, which constitutes 26% of global GDP, and would send forceful international shockwaves.

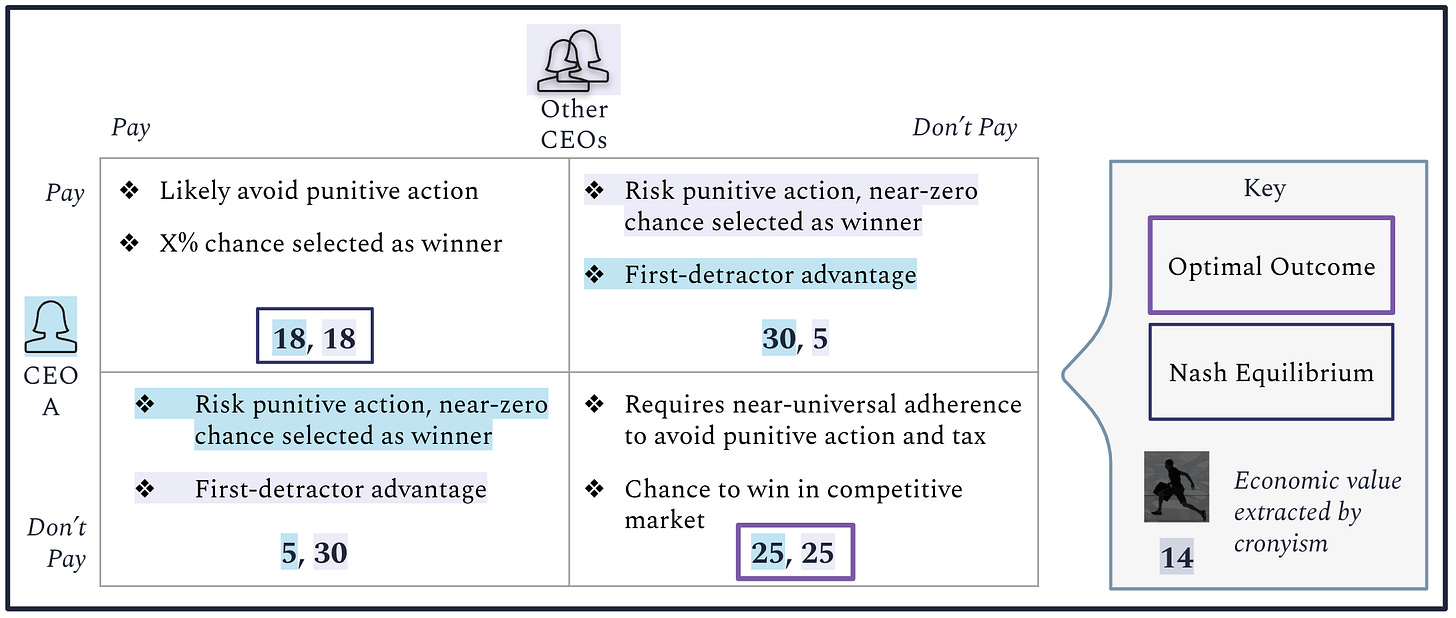

A more commonplace game theory scenario shows us that without state intervention in the form of harsh penalties for abusers, individual actors shift from lawful behavior toward cronyism. As depicted in the mock-up below, we land at a Nash Equilibrium that includes suboptimal outcomes for individuals and the economic system as whole.

Even though all parties benefit from near-universal adherence, avoiding punitive action and a bribery tax, the first detractor advantage incentivizes individuals to break from the anti-bribery pact. Once individuals detract, those left in the pact risk punitive action and can only improve their positioning by joining in bribery, ultimately arriving at a suboptimal Nash Equilibrium. When central authorities reap the benefits of cronyism instead of enforcing rules and punishments, value is extracted from the system and consolidated by the powerful.

From Dabla-Norris and Liu’s game theory methodology, we learn how to isolate variables and better understand the scenarios in which firms choose to pay illegal bribes.1213 Of particular salience, Dabla-Norris's analysis concludes that “the self-interested behavior of central authorities determines the optimal level of corruption in the hierarchy,” highlighting the fragility of behavioral norms and inevitability that individuals and firms will break existing laws if doing so is permissible. Applying this rationale to the United States, we observe President Trump at the top of the executive branch's regulatory hierarchy, not only permitting violation of anti-corruption law, but demanding that anti-corruption laws go unenforced. In the case of NYC Mayor Eric Adams, Trump’s Department of Justice accepted resignations from officials who refused to carry out the personally and politically motivated order to drop charges against Adams.14

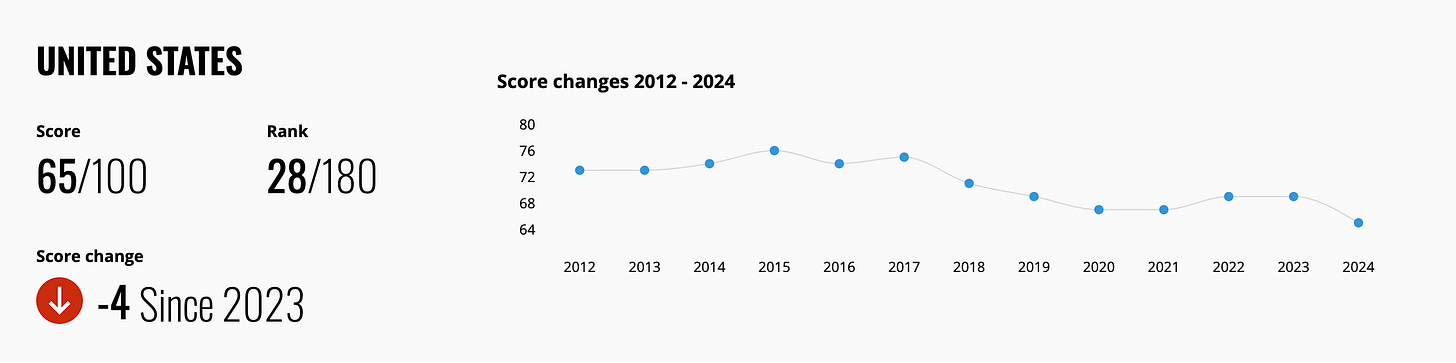

Skeptics are free to push back on my diagnosis of crony capitalism. Are these just buzzwords motivated by political partisanship, or perhaps even hollow words understating the ills of capitalism? Verbiage aside, uncontroversial economic principles and empiricism drive the analysis in this piece, and a litany of peer-reviewed literature has been published on the harms of corruption in developing nations. It’s time for the United States, a nation ranked 28th globally in the 2024 Corruption Perception Index, to abandon its exceptionalism, and let objective, good-faith investigators evaluate the pervasiveness of corruption and cronyism.15

Pushing past ideological differences to reach candid inquiry, we may discover that crony capitalism in the United States predates Donald Trump as a politician or businessman, and that crony capitalism is an institutional and global problem, not a partisan one. We should endeavor to eliminate it from our political system without falling into a trap of partisan finger-pointing. Corrupt actors such as former-NJ Senator Robert Menendez and NYC Mayor Eric Adams, both Democrats, face serious consequences.16 At the same time, we must acknowledge that Elon Musk and Republican President Donald Trump pose a unique and unmatched present threat as a public-private sector duo, due to the powerful levers they control and the asymmetric information at their disposal - not to mention their conflicts of interest.1718